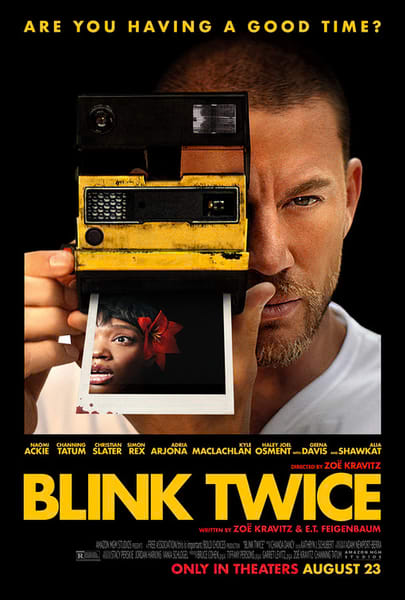

**Spoilers for Blink Twice**

At first glance, Blink Twice, the directing debut from actress Zoë Kravitz, looks like a Glass Onion clone: A tech billionaire (Channing Tatum, in this case) invites a bunch of his friends to party on his private island, but everything is not as it seems. Both movies mine this premise for satire, but where Glass Onion was more lighthearted, depicting Edward Norton’s character, Miles Bron, as a bumbling, fraudulent genius who has failed upwards and stolen all his best ideas (the Elon Musk parallels were not particularly subtle), Tatum’s Slater King is far more sinister. And once the details of his plan were revealed, all I could think about was its echoes of real-world conspiracy theories.

Blink Twice’s point of view character is Frida (Naomi Ackie), who parlays a catering gig at Slater King’s fundraising gala into an invitation to the getaway on King’s private island. Frida and her roommate, Jess (Alia Shawkat), trade their waiter uniforms for cocktail dresses, and Frida quickly catches Slater’s eye. It appears as if Slater has fallen under Frida’s charms, but as the movie later reveals, this is not the first time they have met, and something much darker is at play.

After they arrive at the island and everyone surrenders their cell phones (the getaway is presented as a distraction-free paradise), Slater shows Frida to her room and tells her to freshen up and get ready; everyone will be hanging out at the pool. In her bathroom, she finds a perfume made from the Desideria flower, which Slater tells her only grows on this island. Frida spritzes herself, puts on the white bikini that all the female characters will be wearing for most of the movie, and heads off to the pool with Jess and the others.

The next section of Blink Twice is a blur of swimming, eating, and partying, with jump cuts indicating we are skipping over certain repetitive sequences; the effect is of endless carefree debauchery, with characters admitting they cannot even remember what day it is.

While Frida explores the grounds one day, she runs into a housekeeper, who offers her a drink. Despite the language barrier, she accepts, and only afterward learns that the drink was made from the venom of the snakes infesting the island.

Minor memory gaps crop up during the party scenes, such as Jess’s lighter repeatedly ending up in different hands, often without them recalling when they took possession of it. This phenomenon quickly ramps up, however, after Jess is bitten a snake. Slater says it is venomous, but insists she will be fine. The next morning however, Jess has disappeared, and Frida is the only one who remembers her.

**Content warning for sexual assault and exploitation**

The plot spirals rapidly from there, with Frida recovering more memories, and finding polaroid pictures, that show the men repeatedly assaulting the women on the island. The Desideria flower blocks traumatic memories, so as long as the women kept using the perfume in their rooms, they would remain unaware of the men’s crimes against them.

It turns out, though, that the snake venom is a natural antidote to the Desideria—that’s why Frida remembers Jess when no one else does. Once she realizes this, Frida gets the other women to drink shots made with the venom, and as their memories resurface, they take their revenge.

To recap: Blink Twice is a movie where rich and powerful men lure unsuspecting women to a private island so they can assault them without consequence, until the victims discover the truth and murder their oppressors.

The twist in Blink Twice is barely even a metaphor: Slater King’s island plan is an elaborate form of date rape. Its blunt power doesn’t need to be mapped onto a larger issue. The proximity to the situational threat awareness women have to live with every day is the point. But I couldn’t stop there.

I listen to a few podcasts documenting the depths of conspiracy mania the world (United States in particular) is falling into, especially QAA (formerly QAanon Anonymous), and Knowledge Fight, which chronicles the travails of Alex Jones and his followers (their work was cited in the Sandy Hook judgment against Jones). A cornerstone of these conspiracy-obsessed subjects is what QAA calls “baking,” where a theorist, usually on YouTube, Reddit, Twitter, or even-less-reputable sites, will take a seemingly innocuous headline and massage, twist, or otherwise extrude it into something nefarious.

One infamous example is when they convinced themselves ordering pizza was code for procuring trafficked children, with toppings denoting the kind of child you wanted. This metastasized into PizzaGate, which escalated into a man shooting at a pizza parlor he believed was harboring child slaves in the basement. (The building didn’t have a basement.) Similar “save the children” hysteria erupted over Wayfair furniture, where a brief error in the list prices on their website prompted a frenzy of accusations; if you bought an Olivia crib, the conspiracists screamed, it would include a little girl named Olivia.

One of Alex Jones’s favorite baking techniques is to treat Hollywood movies as veiled confessions of the New World Order’s plans for domination and subjugation. When Leave The World Behind premiered on Netflix, for example, he interpreted the movie’s apocalyptic scenario of technology going offline and throwing society into chaos, with ships running aground on beaches, planes falling out of the sky, and a tween unable to stream the series finale of Friends, as the Satanic NWO being so confident of their coming dominion that they were brazenly boasting about it for everyone to see.

All of which brings me back to Blink Twice. It was hard for me to watch a movie about rich men luring young women to a private island where they will be drugged and assaulted as anything other than an Epstein Island parable. I went beyond even that, imagining the Desideria flower/snake venom dichotomy as an update on the red pill/blue pill choice from The Matrix. Conspiracists co-opted that, too, twisting the Wachowskis’ deliberate metaphor for confronting trans identity into a marketing ploy for whatever supplement or secret knowledge they’re peddling at the moment.

When the venom does its work on the women of Blink Twice, dissipating their amnesia to the horrors committed against their bodies, they respond by violently overthrowing the tropical patriarchy and burning Slater King’s mansion to the ground. Alex Jones will insist he’s not inciting his listeners to commit terrorism, but it’s usually with a verbal wink; they both know what he really means.

As I watched the conflagration at the end of Blink Twice, my first reaction was not empathy for the real women who live through harassment and abuse every day, to the point that violence might be their only recourse, like it was for Chrystul Kizer. it was, “Shit, the worst people on the internet will use this to justify whatever persecution fantasy their online avatars dream up.”

I don’t believe in conspiracy theories; it’s more that I find it fascinating to imagine and investigate the kinds of people willing to go to such lengths to explain the world. My detached hobby was more fun when I grew up watching The X-Files with my dad and brother. It’s less enjoyable now that those kinds of ideas are part of the national public discourse, and officials with “Spooky Mulder” tendencies are clinging to positions of real power and influence.

Even though I don’t believe them, interacting with conspiracies so often, at increasing severity, has rubbed off on me. My reaction to Blink Twice proves that. I don’t want to unsubscribe from that part of my life, because I need something to listen to at work, but also because ignoring the bad people perverting truth with alternative facts won’t make them go away or lose their influence. There has to be a way to counter their rhetorical pollution without it infecting everything I watch and hear. I’m just not sure what that is yet.